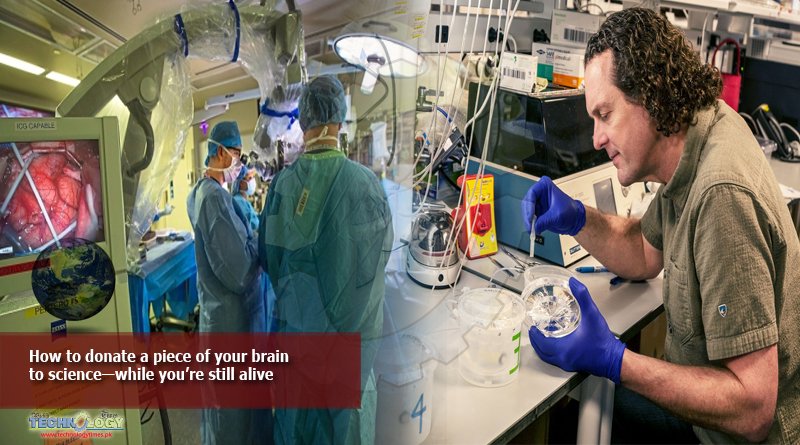

Donating a piece of your brain to biomedical research has never been easier. Scientists have developed a successful live donor program, where patients undergoing brain surgery can contribute a piece of their brain that would otherwise be tossed away.

How does a piece of brain go from the operating room to the lab?

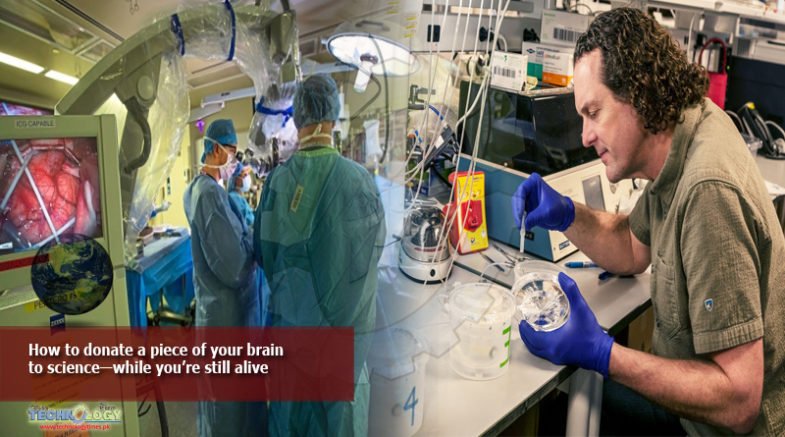

It happens very quickly, Lein says. All the samples he works with are from donors who are going under neurosurgery to treat epilepsy or to remove deep tumors. Once surgeons remove the sugar-cube-size tissue samples, researchers have to transport them quickly to the lab and keep them in a medium with nutrients so they remain alive. Lein and his team get about 50 brain samples a year.

Why are these samples so precious?

The brain “is extremely cellularly complex,” Lein says, “but at the same time, finite and indefinable.” If each cell type in the brain can be identified and described in detail, neuroscientists can understand the role every neuron plays.

Cell cultures and rodent studies offer a lot of information about what happens in the brain in health and disease, he says, but to understand the human brain scientists need to experiment on human tissue. Postmortem samples are a great way to study the anatomy of the brain, but living tissue allows neuroscientists to understand three key functional features of neurons: what they look like, how they fire, and what their genes are doing. This “trifecta” helps researchers to monitor how adult human neurons behave in real time, Lein says, which is important to make sense of the brain circuits that underlie cognition and behavior.

Ultimately, he says, scientists can also use these living brain tissue to understand disease and develop novel therapies.

What makes the human brain different from the mouse brain?

“On the one hand, things are really quite similar,” says Lein. Each cell type looks very much the same. “But on the other, the details of those types of cells vary significantly across species.”

One of the major differences lies in serotonin receptor genes, Lein and his team found last year. Serotonin is involved in major depression and is the target of antidepressant drugs. It’s also involved in anxiety and many other disorders. “It turns out the receptors that are turned on by serotonin are among the worst conserved between mouse and human,” Lein says. That could be a major reason why some new drugs that work in basic studies in mice fail in clinical trials.

How easy is it to donate a chunk of your brain?

“There’s not a uniform way in the in the U.S. really to donate your brain, much less brain tissue,” says Karen Rommelfanger, a neuroethicist at Emory University. But if donors want to do it, she says, they should be able to. “They feel it’s a way for their illness to help others.”

Rommelfanger also mentioned that patients need to “truly volunteer,” and have a say in how researchers will use their tissues. “This is what prevents humans from being reduced to a reserve of tissue, organs and body parts.”

Even postmortem donations are very challenging. If people are organ donors, they can donate their organs after death, but that doesn’t apply to the brain. “It’s really an onerous process,” Lein adds. Researchers need to connect with the family for consent and try to work with medical examiners to have access to autopsy specimens.

Moreover, in some East Asian cultures, a body has to buried with an intact brain, Rommelfanger notes, so researchers also need to take cultural traditions into account. “The tissue itself has an intuitive meaning or a cultural meaning.”

Those who want to donate to the kinds of studies Lein does need to be part of a special program and have to be slated for surgery already, Rommelfanger says. Other research institutions across the world that perform these brain surgeries are starting to develop their own living tissue donation programs.