NASA has funded detailed analyses of four potential projects so the agency can better understand the possible risks and opportunities of each proposal.

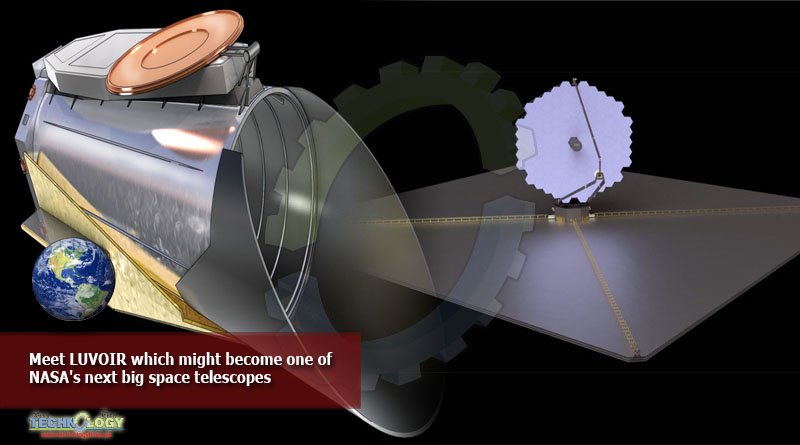

One of those mission concepts is called the Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor (LUVOIR). If it’s built, the telescope could tackle a host of science topics, but its specialty would be giving scientists the most realistic view yet of exoplanets that are superficially “like Earth” but actually like — well, nobody knows.

“Success in this endeavor would be the birth of a brand-new field of comparative astrobiology,” Aki Roberge, an astronomer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland and the study scientist for the LUVOIR mission concept analysis, told Space.com.

If LUVOIR becomes a reality, the instrument’s core contribution to that field would be to produce a detailed view of planets that currently fit scientists’ bare-bones criteria for Earth-like planets. These worlds mimic our home in terms of size, mass and orbit — when scientists know even that much about them. But with LUVOIR observations of just 28 of those worlds, Roberge said, scientists should be able to start understanding how precious our vibrant planet really is.

“Exoplanets are small, black shadows to us, not pale blue dots,” Roberge said. A mission like LUVOIR would change that by gathering enough data for scientists to start looking at so-called Earth-like exoplanets in a statistical, population-wide way.

That’s a similar change in perspective to what the Kepler Space Telescope mission did for exoplanets in general: It identified so many new worlds that astronomers could begin to understand the relative quantity of, for example, massive planets orbiting very close to their stars as opposed to small, rocky worlds.

LUVOIR would zoom in on such small, rocky worlds and tell scientists what proportion of superficially Earth-like planets are actually like Earth, with surface water, an atmosphere and growing organisms.

“We have no idea what the diversity of terrestrial planets is going to be like,” Roberge said. “In the solar system, we’ve got Venus, Earth and Mars. But they’re very different from each other, first of all; second of all, I’m sure there’s other options out there, too.”

For each of the worlds it studies, LUVOIR would produce not images but spectra — breakdowns of the amount of light of various wavelengths coming from the object. Those spectra would allow scientists to identify the compounds on that world, revealing more about what’s happening on the surface.

The LUVOIR team has calculated that if scientists can conduct those analyses on at least 28 small, rocky worlds that turn out to have atmospheres and they see no signs of life, that should be enough information to tell them that less than 10% of planets with the size and orbital characteristics of Earth host life.

If such an analysis does identify life, scientists can begin working on an even larger puzzle, Roberge said: understanding the laws of life. “We have a glimmer of one; it’s evolution as mediated by natural selection,” she said. “There probably are more, but we’re never going to figure out what they are unless we have more examples of independent evolution.”

Beyond habitable worlds

LUVOIR’s main objective would be to discover and examine alien planets to understand the ubiquity of life, but the telescope would find plenty of other worlds as well. “For every habitable planet candidate we discover, we get 10 times as many other exotic exoplanets just coming along for the ride,” Roberge said.

To be a flagship mission concept, however, studying exoplanets won’t be enough; the LUVOIR team also needed to make the telescope’s design relevant to many different subfields of astrophysics. That meant the concept team needed to hone the proposed instrument suite to be as flexible as possible. “All of our instruments play together; we don’t have any instruments that are one-trick ponies,” Roberge said.

The mission concept team also designed a dozen sample science projects spanning the scale of the universe to include in the mission concept spanning the scale of the universe. Those examples are not an ironclad plan for LUVOIR should it be built, but the team wanted to show off the work the telescope could do, ranging from studying dark matter, to showing how galaxies work, to monitoring icy moons in the outer solar system for plumes of water gushing out through their frozen shells.

If NASA decides to select LUVOIR as its next massive space telescope project, the mission would follow a complicated history of proposals. Its predecessor, the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), has been canceled repeatedly in budget requests from President Donald Trump’s administration and reinstated by Congress. Another predecessor, the James Webb Space Telescope, is long delayed and far over budget, at best launching in March 2021.

The scientists and engineers behind LUVOIR have turned that experience with Webb into 10 recommendations they believe will keep their project on track. Not all of those strategies are fully within the control of the team; some would require NASA to revisit its agency policies. And the LUVOIR team believes that, if NASA selects the project, the recommendations will help them avoid meeting a similar fate.

But Webb, which astronomers also refer to as JWST, is still looming over LUVOIR, Roberge said. “JWST has been a challenge for us the whole time,” she said. “I have spent the last four years listening to everybody and their cousin tell me what went wrong with JWST.”