One medical story dominated headlines for virtually all of 2020: the coronavirus pandemic. Here are the accomplishments that may have flown under the public’s radar in 2020.

By Erika Edwards

One medical story dominated headlines for virtually all of 2020: the coronavirus pandemic.

But while Covid-19 did slow down medical story or research in other areas, the science didn’t stop. Researchers rolled out new ways to cope with common diseases, and even a treatment for another feared virus.

Here are the accomplishments that may have flown under the public’s radar in 2020.

A treatment for Ebola

Six years ago, the world had its eyes on a different virus: Ebola, in West Africa. In October, the Food and Drug Administration approved Inmazeb, the first treatment for the deadly disease.

Inmazeb is a monoclonal antibody cocktail made by the drugmaker Regeneron. A study that began in 2018 during an Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo showed that the drug improved survival rates; researchers found that nearly 34 percent of patients who received Inmazeb died, compared with 51 percent of patients who received a control.

Monoclonal antibodies are made in the lab to mimic the body’s natural immune response. This year, Regeneron also developed a monoclonal antibody cocktail for Covid-19, which President Donald Trump received when he was hospitalized with the illness.

In December, the FDA approved a second treatment for Ebola, another monoclonal antibody drug called Ebanga, made by Ridgeback Biotherapeutics.

Weekly insulin shot

People with Type 2 diabetes may find reprieve from daily shots with an experimental form of insulin. In September, researchers at the Dallas Diabetes Research Center found that a once-weekly insulin shot was able to lower blood sugar just as well as a daily insulin shot in those with Type 2 diabetes.

The research, while relatively small with just 247 participants, was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The hope is that patients with Type 2 diabetes will be more likely to adhere to a once-a-week injection than a daily shot.

One pill to cut the risk of heart problems

A single pill that combines four medications meant to lower blood pressure and cholesterol plus an aspirin was found in November to cut the risk of heart disease, the nation’s No. 1 killer.

A large study of 5,713 participants published in November found that the so-called polypill cut the risk for heart attack and stroke in at-risk patients by nearly a third.

The polypill used in the study was a combination of a statin called simvastatin, a beta blocker called atenolol, a diuretic called hydrochlorothiazide and an ACE inhibitor called ramipril. All are sold as generics, which means this could be a low-cost method of treating patients at risk for heart events.

What’s more, patients may be more likely to comply with their doctor’s orders if they need to fill and take only one pill, instead of four.

A blood test to look for Alzheimer’s disease

The test, from C2N Diagnostics of St. Louis, Missouri, measures two types of amyloid proteins — generally considered a hallmark of Alzheimer’s — and looks for evidence that a person has a genetic risk factor for the disease.

It is meant for people 60 and older who are having memory issues and who are being evaluated for Alzheimer’s. It is expensive ($1,250) and not covered by health insurance. Results are generally expected within 10 days.

Data on the test’s accuracy have not been made public, and it is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Outside experts remained cautious, but said that even if the blood test were to show a low likelihood of true Alzheimer’s disease, it could give doctors a clue that something else might be causing memory problems, such as side effects of medications or even vitamin deficiencies.

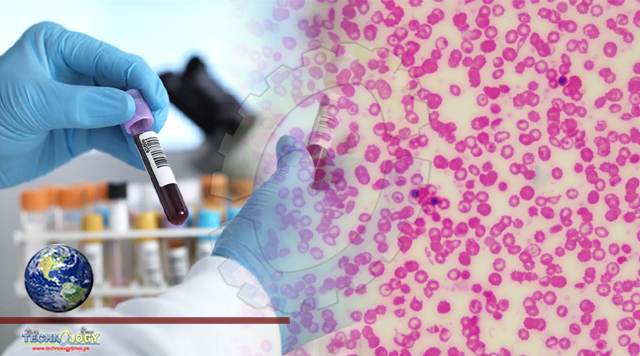

Towards a cure for sickle cell disease

Early December brought early but promising results from the first studies on gene editing for excruciatingly painful and inherited blood disorders most likely to occur among those of African descent.

The technology, called CRISPR, involves permanently altering DNA in a person’s blood cells. The approach could possibly cure sickle cell disease, in which crescent-shaped red blood cells clump together to the point that they’re unable to flow easily throughout the body, starving organs and tissue of the oxygen they need.

Using CRISPR, doctors are essentially able to switch off a faulty gene that creates the problem. In studies, 10 patients were able to remain without pain episodes for at least several months, and were able to be free of regular blood transfusions previously necessary to treat their disorders.

The only other potential cure for sickle cell disease involves a complicated bone marrow transplant from a closely matched donor who does not have the disease.

Pediatric heart hope

One of the last advances of 2020 was the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a heart pump to be used in children in need of a heart transplant.

Abbott’s HeartMate 3 heart pump is meant for children with a specific condition called advanced refractory left ventricular heart failure that requires a full heart transplant. Without intervention, the condition is deadly, as the heart is too weak to pump on its own.

Two years after the implant — which is permanent — Abbott said patients who received the pump had a 79 percent survival rate, comparable to those who received a heart transplant.

But patients who receive heart transplants must be put on medications to suppress their body’s natural immune response to attack the new heart for the rest of their lives. A device like Abbott’s does not require such medication.

Originally published at Nbc news